Places

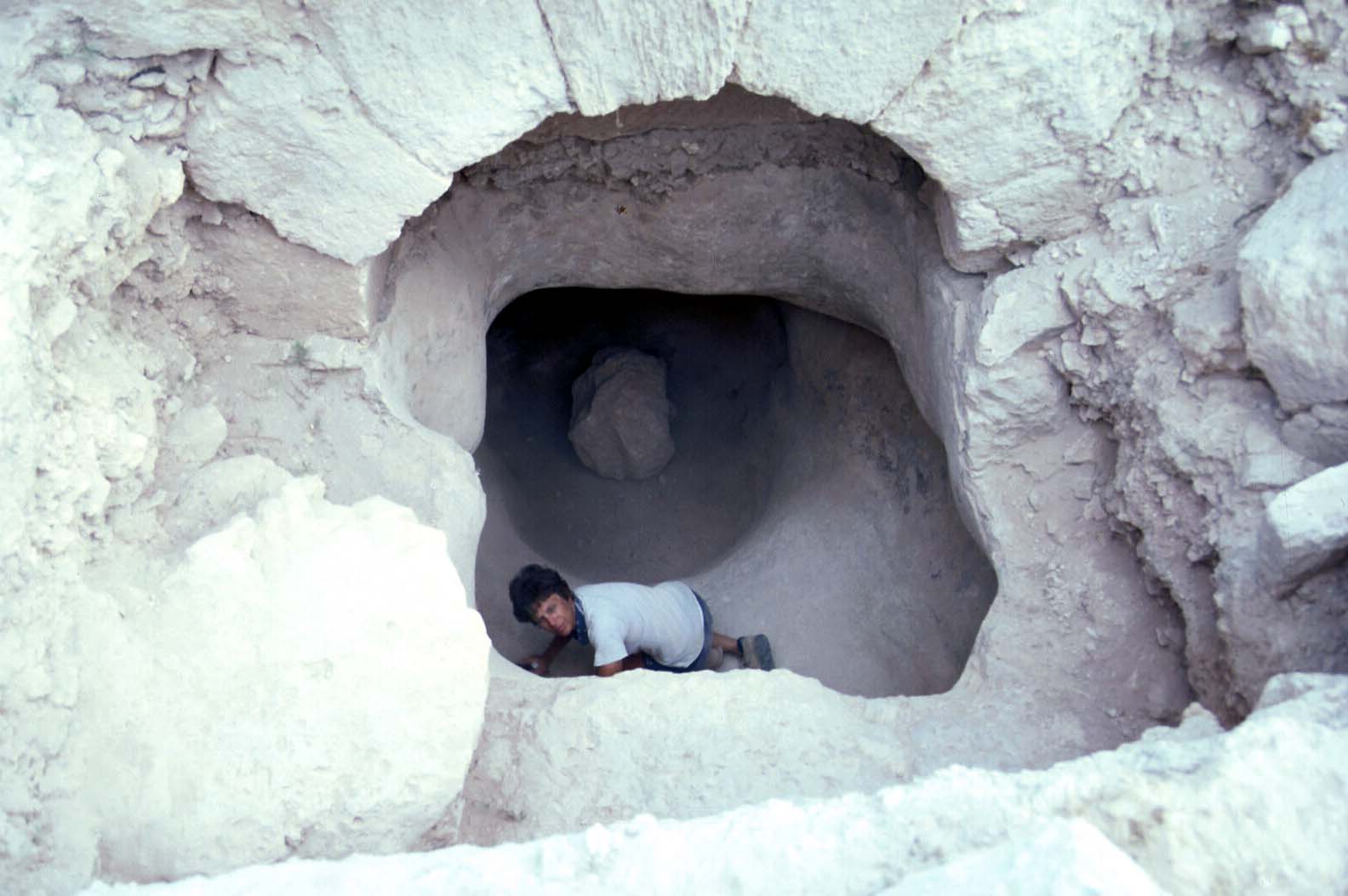

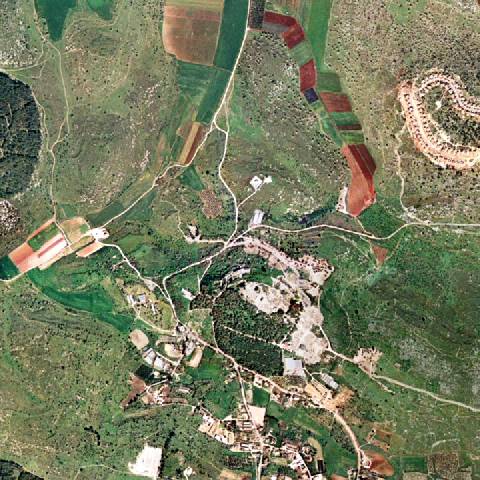

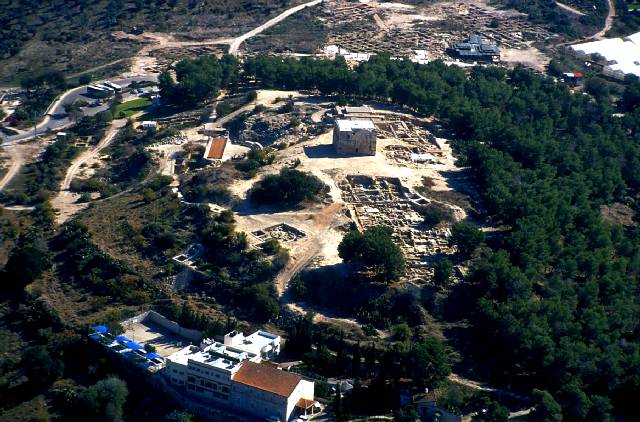

SepphorisAlternative names: Diocaesarea, Tzippori, Zippori, AutocratorisPlace descriptionThis is one of the two main Jewish Galilean cities mentioned by Josephus after the biblical period (Life 346; Antiquities 13.338). Aviam has suggested that Sepphoris was the place where Alexander Janneus was raised in the Galilee, according to Josephus’s story (Antiquities 13.323; Aviam 2000). The city’s name was first mentioned in the battle between Ptolemy of Cyprus and Janneus. From that point on, Sepphoris was mentioned in connection with almost every major event that took place in the Galilee: it became the capital of the Galilee under Gabinius in 63 BCE; Herod conquered it in 38 BCE in his first campaign in the Galilee; and the city was badly damaged in the Varus revolt in 4 BCE when Judas the son of Hezekiah attacked Sepphoris, primarily to gain entry to King Herod’s royal palace and arsenal in order to get arms. The city was later rebuilt under Herod’s son, Antipas, as his capital, no doubt with a large palace and associated royal installations and fortifications, and renamed Autocratoris, the “ornament of all Galilee.” The city was fortified by its citizens at the order of Josephus (in Life 82 he claims to have captured the city twice), but surrendered to the Roman army under Gallus in 66 CE (Life 30, 373, 394); later it opened its gates to Vespasian and the Romans in 67 CE (Life 411). In the early second century CE, prior to the Bar Kochba Revolt, the city’s name was changed again to Diocaesarea. Later it became home to a number of important rabbis including (Judah the Prince, the compiler of the Mishnah) and, for a while, the location of the Sanhedrin. (Nagy et al 1996). In the first century the city was estimated to be about 80 dunams (8 hectares; 20 acres). Although the site has been excavated for many seasons, no final report has yet been submitted, but numerous minor publications are available. <br>The city was built on the round-topped hill (Arabic, Saffuriyeh) overlooking the Beth Netofa Valley to the north. A narrow paved street crossed the site from east to west, with signs of a drainage channel under the road along its southern edge. To the south of this street and just west of the center of the Crusader “citadel” was a Hellenistic building (barracks?); there was also evidence of bath facilities, and southeast of the Citadel a possible public building. Sepphoris had two aqueduct systems, the earlier one dated from the early first century CE, probably when Herod Antipas rebuilt the city (possibly from late in Herod’s reign); its elevation was somewhat higher than the later aqueduct, though not high enough to supply water to the hilltop; most houses collected water in cisterns, as in other sites (Tsuk 1999). A market (agora) was on the hilltop; later a second “lower agora” was built to the east.<br>Archaeologists still debate whether the theater, on the north slope of the main hill, was built in the first or second century CE; the late-first century seems likeliest (for an architectural description of the theater, without discussion of dating, see Netzer and Weiss 1994). In the residential area on top of the hill, especially on the western side of the site, first-century houses with mikvaoth were found, pointing to Jewish life in this period. One fairly complete house survived in Insula II in this area, with a reception or dining room decorated with vegetative frescoes and plastered floor (covered by a layer of ash); beside it was a kitchen or storage room, and beside that a mikveh (Hoglund and Meyers in Nagy 1996: 40).<br>The city soon began to develop towards the east and south. By the first half of the second century CE Sepphoris included substantial areas on the east, which have been extensively excavated, disclosing insulae on a Hippodamian plan around a Cardo Maximus and two Decumani. These streets were connected to the earlier hilltop street pattern. A very large public building (40x60 m.) Was erected at the base of the hill and west of the main street in the early-first century CE, perhaps at the turn of the century. This was constructed on a basilical plan, using in its lower courses typically Herodian “drafted” masonry with well-defined margins, with pools and fine mosaic floors. Its purpose is still unclear; one suggestion is that it was an upscale market (Strange in Nagy 1996: 117-21). Two bath buildings along with other major structures, many of which have brilliant mosaics, give a clear impression of the later developments. This eastern portion of the site does not, for the most part, reflect the Sepphoris of Josephus’s day, however. Massive cisterns characterized the impressive second aqueduct system, which provided water mainly to this eastern part of the city.<br>Small Finds. A fine black-glazed rhyton (drinking cup) from the fourth century BCE, terminating in a winged lion-like creature was found by chance on the site, as well as a fragment of a jar with seven letters in Hebrew from the second century BCE (possibly referring to an epimeletês or “overseer”). In bronze, a light-hearted bronze relief plaque from the first century BCE or CE with a winged figure riding a horned goat behind a table or altar, and bronze statuettes of Prometheus and Pan in the residential area on western side of site (second-third century CE) were also found (Nagy 1996). Other bronze finds included an incense burner, bowl for the incense, and a bull. On an undated lead market weight, the apparently Jewish names “Simon son of Aionos and Justus son of…” were found. A collection of pottery incense shovels (second-third centuries) was found on the western portion of the site.<br>Tombs. In later periods the cemetery of Sepphoris was one of the major burial areas of the region, rivalling the cemetery of Beth She`arim in its size. Little evidence of first-century burials has been found (Weiss in NEAEHL 4:1328 for second and third century CE tombs). Stone ossuaries, found in one of the recently excavated tombs, demonstrate Jewish burial customs in the second century CE, as do Jewish inscriptions in some tombs. The stone sarcophagi reused in the Crusader building were probably robbed from the tombs on the southern hill. A monumental mausoleum is still visible to the west of the hill.<br>Coins. Under Herod Antipas the coins minted at Sepphoris did not use any figurative art. At the time of the First Revolt the coins of Sepphoris carried the inscription “Neronias” and “Eirenopolis” (“City of Peace”), alluding to its wish for peace by surrendering (“Under Vespasian, in Neronias-Sepphoris-Eirenopolis,” from 68 CE). After the revolt, the coins were similar to other pagan city coins; for example, under Trajan the coins carried a laurel wreath, palm tree, caduceus, ears of barley. Images Sepphoris cistern below theatre ZW  Sepphoris Hellenistic houses W Acropolis ZW  Sepphoris Hill of 1st cent city ZW  Sepphoris miqveh under Dionysius House ZW  Sepphoris pre-theatre ceramic vessels ZW  Sepphoris Roman colonnaded streets E of hill ZW  Sepphoris theatre on N slope ZW  Sepphoris.Diocaesare  Sepphoris  Sepphoris Roman cardo overview, tb  Sepphoris 1st century city, zw  Sepphoris water channel SM  Sepphoris aerial from west, tb  Sepphoris mosaic of Mona Lisa, tb Passages - Flavius JosephusThe Judean Antiquities (Whiston)The Judean War (Whiston)The Life of Josephus (Brill)The Life of Josephus (Whiston) |